L’Emilia-Romagna è spesso citata come esempio virtuoso di sviluppo industriale fondato su piccole imprese e cooperazione pubblico-privato. Questo articolo ricostruisce l’evoluzione della visione e della politica industriale regionale dagli anni ’50 a oggi, mostrando come la capacità di adattamento abbia sostenuto la resilienza economica. Ma emergono nuove criticità: frammentazione produttiva, precarietà del lavoro, diseguaglianze crescenti. È tempo di aprire la governance regionale a nuovi attori per affrontare le sfide del futuro?

Alberto Rinaldi e Giovanni Solinas – Giugno 2025

Emilia-Romagna (ER) is a paradigmatic case of industrialization based on SMEs (Brusco 1982; Piore & Sabel 1984; Best 1990). Differently from other Italian regions with a similar industrial structure (i.e., Veneto), industrial development in ER was sustained by industrial policy of local governments since an early stage. ER is also a case of political stability as since the end of WW2 all major local governments in the region have been controlled by the same party: until 1991 the Italian Communist Party (PCI), then its successor parties (PDS, DS, PD).

Within this context, the main aims of this paper are the following:

- To investigate the role of SMEs in the analysis (vision) of ER’s ruling party;

- How this vision changed over time;

- How this vision informed the local governance structure and industrial policy in ER;

- How industrial policy fostered structural change and economic resilience in the region;

- How the emergence of some critical points in recent years might require a new change (or, at least, a refinement) in the vision and in the governance structure in the region.

The originary positions

After WW2, the position of the PCI towards SMEs was set by party’s leader, Palmiro Togliatti, who profoundly innovated with regard to the traditional thinking of the Left. According to Togliatti (Brusco & Pezzini 1990):

- Large firms and small firms produce homogeneous goods;

- Large-scale business is the most efficient form of production, but it may lead – as it had occurred in Italy – to the creation of monopolies (or oligopolies) that limit output to maximise their profits. This made Italy a case of “blocked development”;

- Small firms are small because they have not yet grown. As long as they remain small, they are inefficient. Some small firms will successfully grow and become large and competitive, whereas many others will fail;

- In any case, small firms counteract the block to development imposed by monopolies;

- The PCI must support small firms because their growth prompts development, employment, wages and the living standard of the working class;

- Small entrepreneurs are (or should become) strategic allies of the working class. In Togliatti’s view, this alliance strengthens democracy as it helps to steer away small entrepreneurs and middle classes from the influence of right-wing (neo-fascist) forces.

Governance and industrial policy: 1950s-1970s

In the wake of Togliatti’s analysis, the PCI promoted the formation of left-wing organizations not only for workers and labourers, but also for small entrepreneurs (artisans, shopkeepers, farmers, sharecroppers) and cooperatives.

Togliatti’s view was the reference point for the governance structure and industrial policy in ER in the 1950s-1970s. As to the governance structure, the PCI ordered stakeholders according to their closeness (distance) from the working class. On the basis of this ordering, the party decided which stakeholders to include (exclude) in (from) its system of alliances and in the political process that led to the definition of public policies: left-wing organizations were in, the others were out (Bellini 1989).

Prior to the establishment of the regional government in 1970, industrial policy in ER was enacted by municipalities and provincial governments and aimed at fostering the size-growth of SMEs through a variety of actions: the creation of industrial estates for SME settling; investment in technical and vocational education; access to credit (Brusco & Righi 1989, Capecchi 1990).

The discovery of industrial districts

In the late 1970s-early 1980s a new vision of local development emerged in the Emilian PCI: the discovery of industrial districts (IDs) in the wake of studies by economists (Becattini 1979; Brusco 1982; Piore & Sabel 1984). ER was seen as a paradigmatic case of industrialization based on IDs. According to this vision, SMEs can be efficient as economies of scale refer to a single stage of the production process and not to a vertically integrated process (Brusco 1975). Moreover, as most SMEs are supplier firms, complementarity between large firms and small firms was now emphasized.

This new vision of local development led the regional government of ER to draft a new industrial policy based on the creation of real service centres to SMEs clustered in IDs. The principal aim of these centres was to provide “real services”, i.e., disseminate knowledge relevant for economic success that SMEs were unable to acquire on the market to prompt an upgrade in IDs. The target unit of this policy was not the single enterprise but the network of enterprises clustered in IDs. The underlying idea was that industrial policy had to transfer a new knowledge into a whole social fabric where it was formerly absent in order to nurture SMEs rooted in it (Brusco 1996).

A new governance structure

The adoption of the real service policy led to a change in the governance structure in ER with the opening of the governing party to the whole spectrum of economic interests. All entrepreneurial associations – including those that were outside of the PCI’s traditional alliance system, such as the Catholic associations of small entrepreneurs and cooperatives and the associations representing larger firms (i.e., Confindustria and Confagricoltura) – entered the capital structure and board of directors of the new real service centres together with Ervet (ER’s Regional Development Agency) (Bellini 1989).

The fact that the ruling party no longer ordered economic interests in relation to their closeness to the working class led to the establishment of a neo-corporatist concertation in ER (Schmitter 1974): the region’s development agency Ervet and its network of real service centres became the place for dialogue and cooperation between the regional government (and ER’s ruling party) and the whole spectrum of all major established stakeholders. This neo-corporatist concertation laid the basis for a shared vision of local development with the identification of the strengths and weaknesses of the regional economy that framed the region’s industrial policy.

From the industrial districts to the regional clusters of firms

In the late 1990s, dialogue with stakeholders in the frame of the neo-corporatist concertation led to question the long-term competitiveness of IDs in the face of structural shocks as globalization and the ICT revolution. This led to a new shared vision local development (Regional Pact for Labour in 2015) according to which regional clusters of firms hinging on larger firms (lead district firms and MNEs) and no longer IDs were seen as the spine of ER’s economy (Bianchi et al. 2024).

Since 2000, ER’s industrial policy has been re-oriented in compliance with this new vision of local development through a variety of actions:

- The creation of Technopoles (industrial research labs and technology transfer centres). By 2025, eleven technopoles have been established in ER, spread across 20 cities;

- The creation of Clust.ERs (communities of firms, worker representatives and other institutions that reflect and delineate the best future strategic options and policy instruments to support the most important industries in the region);

- The creation of digital infrastructure (the Big Data Technopole in Bologna that hosts one of the top five supercomputers in the world for its computing power);

- Attraction of foreign MNEs in the region. Some significant examples are Lamborghini producing a new SUV given the new investment made by the German firm Audi (Volkswagen Group) to which it now belongs and the investment of Sacmi (packaging sector) and AVL Italia in a research centre on big data. Foreign firms localized in the region have grown in number as a result of this policy, from a few dozens twenty years ago to several hundred nowadays.

- Investment in human capital, with the creation of ITS (a network of technical institutes linked to businesses), new Masters programmes jointly developed by firms and universities (i.e., the MUNER programme in automotive engineering), and vocational courses to foster digitalization of regional firms.

The region has been able to mobilise funding at different levels (national and European, private and) for the implementation of the policy.

Emilia-Romagna: a resilient region

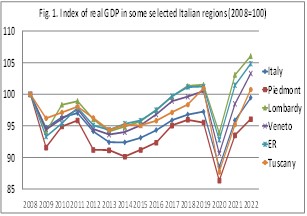

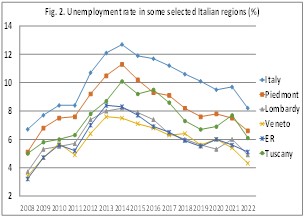

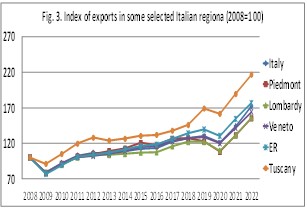

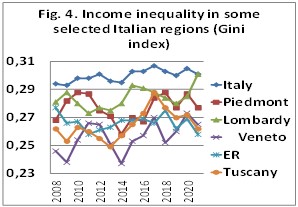

Figures 1 to 4 show that ER performed well in comparison with Italy’s major industrial regions in the face of both structural and sudden shocks that have occurred since the 2008 financial crisis. ER is, together with Lombardy, the best performing region by considering four indicators of economic resilience: real GDP, unemployment rate, exports, and income inequality.

Figure 1. Emilia-Romagna performance in comparison with Italy’s major industrial regions by considering four indicators of economic resilience: real GDP, unemployment rate, exports, and income inequality.

Source: Authors elaborations on Istat data

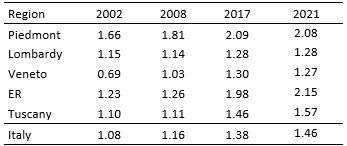

ER also features a high level of innovation. Since 2002 ER outperformed all other four major industrial regions in Italy as concerns the growth of R&D as a ratio to GDP. By 2021 ER came ahead also of Piedmont where Italy’s largest company Fiat has its R&D facilities (see Table 1).

Table 1. Intramural R&D expenditure on gross domestic product (GDP) in some selected regions (%)

Source: Authors elaborations on Istat data

These results can, at least in part, be ascribed to regional industrial policy.

Some critical points

Despite the good indicators of economic resilience displayed in the previous section, some critical points have emerged in the ER’s economy in recent years (Rinaldi & Solinas 2023). These concern:

- Firm demography. Firms in ER decreased from 428,000 to 398,000 (-7%) between 2008 and 2020. Especially smaller supplier firms closed down. This was the consequence of a deep restructuring of local industry whereby lead firms increasingly specialize in upstream and downstream phases of the value chain while manufacture tends to be outsourced away from ER, with the risk of a loss of skills competences;

- Massive reliance on short-term low-wage labour contracts, not only by weaker and marginal firms but also by lead firms, with the risk of disinvestment in human capital;

- Vocational training. According to a recent survey, less than 50% of firms in the region invest in vocational training and less than 20% plan to do it;

- Vocational training centres – that are controlled by the stakeholders of the neo-corporatist concertation – prefer to organize catalogue courses, less apt to reproduce local, often tacit, knowledge;

- Digitalization. Many firms in the region do not adopt KET and, when they adopt them, they do not invest in congruent training;

- Increasing income and wealth inequality;

- Managing of migrant networks;

- Increased presence of the mafias: a break in the “rules of the game” in the region?

Final remarks

The coexistence of resilience and new critical points may induce to hypothesize that the neo-corporatist governance in ER may have led to a “conservative dynamic equilibrium” (Di Tommaso 2020) whereby structural change is pursued to satisfy a number of pre-selected stakeholders that are included ex-ante in the neo-corporatist concertation.

The emergence of the critical points surveyed in the previous section appears, at least in part, the consequence of the exclusion of other stakeholders from regional governance, whose voice is not considered by the policy-maker (and by the ruling party).

The challenge for ER could therefore be to pass to a “transformative dynamic equilibrium”. This would involve the opening of regional governance to new stakeholders leading to the creation of a really pluralist governance able to respond to new social demands. Such a pluralist governance could more effectively foster a structural change which pursues more ambitious and desirable societal goals, i.e., concerning education, health, equality, environment sustainability, etc.

References

Becattini, G. 1979, “Dal «settore» industriale al «distretto» industriale. Alcune considerazioni sull’unità di indagine dell’economia industriale”, Rivista di economia e politica industriale, 5(1): 7-21.

Bellini, N. 1989, “Il socialismo in una regione sola. Il Pci e il governo dell’industria in Emilia-Romagna”, Il Mulino 39, (5): 707-732.

Best, M. 1990, The New Competition. Institutions of Industrial Restructuring, Cambridge: Polity.

Bianchi, P., Giardino, R., Labory, S., Rinaldi, A., & Solinas, G. 2024, “Regional Resilience: Lessons from the Historical Analysis of the Emilia-Romagna Region in Italy”, Business History, 66(8): 1983-2007.

Brusco, S. 1975, “Organizzazione del lavoro e decentramento produttivo nel settore metalmeccanico”, in Flm di Bergamo (a cura di), Sindacato e piccola impresa – Strategie del capitale e azione sindacale nel decentramento produttivo, Bari: De Donato, 7-67 e 203-233.

Brusco, S. 1982, “The Emilian model: productive decentralization and social integration, in Cambridge Journal of Economics, 6(2): 167-184.

Brusco, S. 1996. “Small firms and the provision of real services”, in F. Pyke & W. Sengenberger (eds), Industrial districts and local economic regeneration, Geneva: ILO, 177-196.

Brusco, S., & Pezzini, M. 1990, “Small-scale enterprise in the ideology of the Italian Left”, in F. Pyke, G. Becattini & W. Sengenberger (eds), Industrial districts and inter-firm cooperation in Italy, Geneva: ILO, 219-246.

Brusco, S., & Righi, E. 1989, “Local government, industrial policy and social consensus: the case of Modena (Italy)”, Economy and Society, 18(4): 405-424.

Capecchi, V. 1990, “A history of flexible specialisation and industrial districts in Emilia-Romagna”, in F. Pyke, G. Becattini & W. Sengenberger (eds), Industrial districts and inter-firm cooperation in Italy, Geneva: ILO, 20-36.

Di Tommaso, M.R. 2020, “Una strategia di resilienza intelligente per il dopo coronavirus. Sulla centralità della domanda e offerta di politica industriale”, L’industria. Rivista di economia e politica industriale, 41(1): 3-20.

Piore, M.J., & Sabel, C.F. 1984. The Second Industrial Divide, New York: Basic Books.

Rinaldi, A., & Solinas, G. 2023, “Visione, governance e politica industriale in Emilia-Romagna: un’analisi di lungo periodo”, L’industria. Rivista di economia e politica industriale, 44(1): 3-26

Schmitter, P.C. 1974, “Still the Century of Corporatism?”, The Review of Politics, 36(1): 85-131.